The Story of Night of Silence

Night of Silence is my one composition that continues to evoke questions from all over the world. While many of these questions have been addressed through various media channels (newspaper interviews, magazine articles, online reviews), the full narrative has never been told in one place, and never in my own words. I’ve been waiting for the right platform to share this story, one in which the telling could serve a bigger idea. This website provides that platform.

Night of Silence is unlike any of my other compositions. Its conception is a tale of longing and belonging, for Night of Silence belongs, in part, to so many. It took a tribe to compose Night of Silence and those involved, directly or indirectly, deserve recognition.

the genesis of an idea

The story begins in autumn 1981, while I was a junior at the College of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN (now the University of St. Thomas). I was 21 years old. As a music/piano major, I had completed the requisite four music theory courses but I was hungry for more, so I enrolled in a graduate music theory course. The four courses leading up to this graduate course played a major role in my composing Night of Silence. Analyzing and deconstructing music is a skill every pianist and composer needs if one aspires to any level of innovation. I have college professors Francis Mayer and James Callahan to thank for teaching me these skills. I also have Joe Kozak to thank, one of my early piano teachers, who introduced me to improvisation and composition at a young age.

Note: Dr. James Callahan, my piano professor for four years at St. Thomas, was instrumental in helping me acquire a grant to develop Apple IIe software for the music theory department. This opportunity would eventually lead to a job with Wenger/Coda Music Software and a key role on the development team for the Finale music publishing platform.

The idea to compose Night of Silence came to me during the fall semester. I was attending an off-campus weekend retreat, and we were given the opportunity to spend some quiet time in a small chapel. It was during this time I realized I was losing touch with why I had chosen music as a degree-path. I was experiencing music more intellectually than ever before, and I missed the emotional component.

Something else occurred during this time in the chapel—I was struck by the ambient light that was streaming in through some translucent glass blocks. Even though it was autumn, it looked very much like the reflected white light of a winter snow scene. For that moment it felt like Christmas. The chemistry of this wintry light combined with my inner struggles with music created the spark, the idea to compose a piece that could be sung simultaneously with Silent Night (I didn't realize it at the time, but this type of song is called a quodlibet). Composing partner songs was not new to me. I'd done it a few other times—even once in high school, so Night of Silence was a logical progression of my interest in this form of composition.

st. thomas & liturgical music

During my four years at St. Thomas I was actively involved in the music ministry program, having been recruited by Rob Strusinski, who lead the St. Thomas/St. Catherine Liturgical Choir and Campus Music Ministry program at St. Thomas. One of my roles was to play for midnight Mass on Saturday nights. I would pack up my Yamaha electronic piano, drag it from the third floor of Ireland Hall to the lower sanctuary of the chapel, and meet up with a vocalist and a guitarist. The many musicians and composers I collaborated with for these services included David Haas, Jeanne Cotter, Peter Mayer, John Seiwert, Joanne Wagner, Debbie Denman, Paul Fried, and many others.

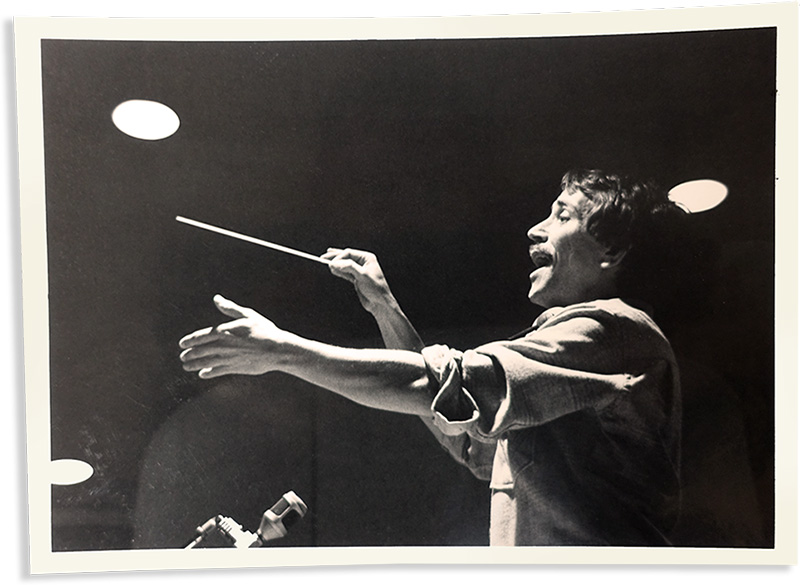

Rob Strusinski, Director of College of St Thomas and St. Catherine Liturgical Choir

Rob Strusinki was my accidental mentor, always open to considering any music I composed. I would not have composed Night of Silence were it not for the culture of innovation and opportunity he created. During my sophomore year Rob produced the InSong album featuring the Liturgical Choir, which included my Lord’s Prayer. Newly ordained Mike Joncas provided the solo voice on the spoken intercession of my piece. David Haas (who also had a piece on the album) and Marty Haugen were also actively involved with the liturgical music program at St. Thomas, drawing upon campus talent for their early album projects. A new era in liturgical music was emerging and Minnesota was a key contributor, if not the leader of this movement. The influences and experiences I enjoyed that year shaped my development and perceptions as a young liturgical music composer. It was a great time to be at St. Thomas.

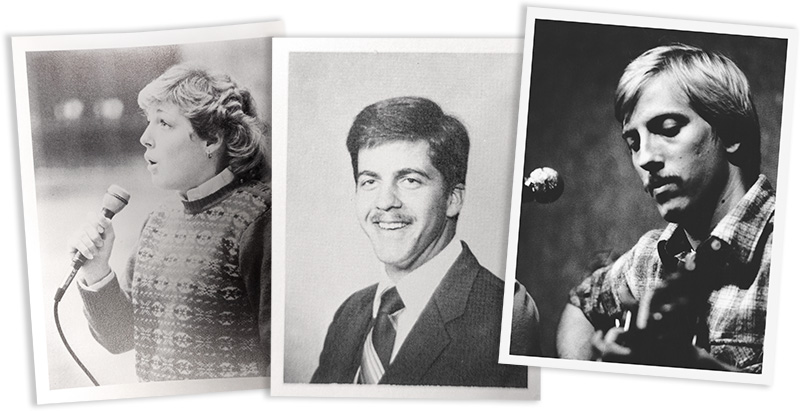

InSong album composers: Front row, L to R: Mark Rumpza, Ron Noecker, Daniel Kantor; Back row, L to R: Mike Joncas, David Haas, Paul Rysavy, Jay McHale, Dr. James Callahan, Rob Strusinski

composing begins

It was a busy semester academically so spending time to compose just for myself was impractical, if not irresponsible, since piano majors were expected to practice three hours a day. However, I found composing therapeutic...and it was freeing. Unlike college coursework there was no one grading my every thought, no one scrutinizing every note I produced, no one judging the musical instincts I wanted to follow.

Composing Night of Silence was a healing, integrative act for me. It leveraged both intellect and emotions in a way that validated the choices I'd made up to that point in my life, reconnecting me to the joy of creating music. Though composing is a solitary activity, it offers the potential for a powerful social feedback mechanism. The performance of a new work connects the composer with hundreds of people at one time. There's a compelling energy to this kind of experience. Visualizing the possibility of this while composing Night of Silence was enlivening.

In hindsight I now realize I was depressed during this time, struggling with my sense of self. Am I good enough? Why am I not enjoying this? Can I survive through graduation? What if people discover I’m a fake? Can I get through my junior and senior solo recitals? What if I bomb? How do I make choices now that will affect the rest of my life? Though I didn’t realize it at the time, composing Night of Silence was my way of dealing with the anxiety of a difficult time.

Yamaha CP-30

I was lucky enough to have a Yamaha electronic piano in my Ireland Hall dorm room. I acquired the keyboard while still in high school. The piano gave me the luxury of quietly composing and practicing through the use of headphones in my dorm room (My roommate and brother, Bob, would argue the rhythmic thunking of the weighted keys was hardly quiet).

Ireland Hall dorm room, 1980; L to R: Joe Willet (in chair), Bob Kantor, Dan Kantor

My compositional process began not with the text but with the music. The first challenge was to reharmonize Silent Night and then compose a new melody for the new harmony, which took a few weeks to perfect. The new melody had to be more than a simple countermelody to Silent Night. It had to stand on its own to mask its connection to Silent Night. It also had to artfully partner with Silent Night while adhering to certain rules of part-writing (avoiding too much parallelism, for example).

Next came the lyrics. The text to Night of Silence was the product of both research and personal expression. One's art speaks first to oneself, as I would learn over the years. My need for a message of hope which would eventually come through in the second draft of the lyrics.

the first draft

By early November I thought I had a reasonable first draft of Night of Silence (though it was not yet titled), so I showed it to Rob Strusinski. I recall him using the words schmaltzy and cliché in his feedback. Bottom line: the text was horrible.

Rob challenged me to lean heavier into Advent. He also suggested I consider the use of metaphor rather than the purely literal when crafting text. To illustrate his point, Rob pulled out a piece from his files that beautifully demonstrated this. It was Mike Joncas' Stars Flung Like Diamonds. I still have the image in my mind that was produced by Rob's reading of those lyrics.

Rob also suggested I draw from my own experiences of Advent and Christmas to make the piece more personal, more intimate.

So, back to the drawing board. There was no Google at this time. No email. No internet. Just phones and snail mail. I did some research in the college library and also wrote to an acquaintance, Dennis Kurtz, whom I knew to be a good resource on matters of ritual. The packet of information Dennis put together for me was invaluable. I have Dennis to thank for his insights on the symbol of the rose, which led to the line “Frozen in the snow lie roses, sleeping.”

I also drew upon my life growing up in northern Wisconsin. Wintertime had always been magical to me, especially Advent and Christmas. My family's home was just a short walk from the stunning landscape of the northwoods where I would often indulge in the quietude of night snowshoeing. There is no other silence like wandering winter woods. Deep snow absorbs sound in a way that makes even a vast wilderness feel intimate and embracing. When seen under a moonlit sky, the light was often bright enough to cast a shadow. The snow would actually sparkle in this moonlight. This effect is depicted in the brief dissonance that can be heard in the piano introduction to Night of Silence (the A against the G-sharp). References to wind, cold, shadows, night, shimmer, and sky are all celebrated in the lyrics, drawn from the mystical imagery of my Wisconsin home.

My sister, Mary, who was then a music and liturgy student at The College of St. Catherine, also offered some insights on the history of Advent and its symbology. She inspired me to craft language that was more poetic and prayerful. Mary always had the knack for creating a voice with both gravitas and approachability. I have her to thank for elevating the imagistic theology of Night of Silence.

the final draft

A few weeks after Rob’s diplomatic rejection of my first draft I presented him with my second draft. To my relief he loved it. Over the next few weeks a few small changes would be made. David Haas, for example, suggested I change the words “my ear” to “the ear” in the line Gentle on the ear you whisper, softly—a subtle, but perfect edit. Only a singer of his caliber would have sensed the need for this nuance. I recall him singing it to me to make his point. Beautiful.

The piece was completed in December 1981. It was too late to use in any services or concerts on campus so I gathered some musician friends to test and record it. Ireland Hall, the dorm where I lived, was just across the upper quad from the chapel where the recording would be made. All I needed was some recording equipment. Across the hallway from my dorm room lived an exchange student from Japan, Terufumi “Teri” Futaba. Teri was a lover of music and owned some great audio equipment, which he was always willing to share. So we used his high-end Sony boombox to produce a crude, but effective cassette tape recording.

L to R: Joanne Wagner Pauley, Dan Swason, John Siewert

Very much like the story of Stille Nacht, we recorded Night of Silence in a cold, dark chapel on a winter's night. I was on piano, with John Seiwert on guitar, and Joanne Wagner and Dan Swanson on vocals. My first experience of the piece that night was heartening. Up to this point it had all been in my head. To hear it with live voices (and actually working) was thrilling. I recall bringing the boombox to the cafeteria the following night to play the recording for the regular dinner gang: Pat Dorn, Ann….Mike Peller, Terufumi Futaba, my brother Bob and his soon to be fiancée, Monique Thouin. The piece was still untitled at this point. That evening in the cafeteria the title Night of Silence was proposed by Mike Peller. It was his idea to reverse the words Silent and Night. While the words Night of Silence are never sung in the piece, it made for the perfect title.

Ireland Hall, as seen from the Chapel

Terufumi’s boombox would make it home to Spooner for Christmas. There were four Kantor kids in college that year, three of us at St. Thomas, one at St. Catherine. We shared a single, very large, 1969 Bonneville station wagon. Our luggage, combined with gifts, was enough to all but overload the car's shock absorbers during the drive home for Christmas. During the trip, we listened to the tape over and over again.

The St. Thomas arches on Summit Avenue

advent 1982

One year later Rob Strusinski used Night of Silence for the first time in a public setting: the college’s annual Advent Lessons and Carols. For this performance, which took place in the St. Thomas Aquinas Chapel, Rob asked me to compose string quartet and oboe parts for Night of Silence, which I was thrilled to do.

NOTE: During the fall semester of 1982, I got to know a young freshman piano major, Jeanne Cotter. It didn’t take long to discover we had a shared interest in piano improvisation and composing. Jeanne and I would spend hours riffing on ideas and possibilities. I eventually tapped her for her thoughts on my new string scores for Night of Silence. She had a hand in the fluid, sustained nature of that score. Even as a freshman Jeanne had great musical instincts. It's no surprise she went on to a have a celebrated career as a pianist/singer/songwriter.

With my new string score complete, Night of Silence was ready for its premiere. It was programmed as the final piece of the Advent Lessons and Carols service. Instrumentation featured a small ensemble of unison voices and a solo guitar (just as Stille Nacht is said to have been performed the first time). Strings and piano were added over verses 2 and 3, with Silent Night coming in toward the end of the piece. While Rob Strusinski conducted the choir, he turned around on the podium to invite the assembly to add Silent Night. I was sitting in the assembly with some friends, and Rob managed to catch my eye. He had tears in his eyes. Night of Silence was officially born, a piece conceived a year prior in a small dorm room just a few hundred feet away.

The Chapel of St. Thomas the Aquinas

a surprise in the mail

Having survived my senior piano recital I graduated in the spring of 1983 and moved back home to Spooner. Not sure what to do with a degree in music, I taught piano lessons and worked a job as a teller at the Bank of Spooner. Sometime during that year at home I received an unexpected package in the mail from a company I'd never heard of: GIA Publications. It was a contract for publication of Night of Silence. As it turns out, Rob Strusinski submitted it to GIA without my knowing, along with his strong recommendation. Of course I signed the contract and dedicated the piece to my family, the source of my love for Advent and Christmas.

Had Rob not submitted Night of Silence to GIA, it's likely it would still be sitting in a storage box somewhere, lost and forgotten.

Until the GIA contract arrived I'd never paid any attention to the business of music publication. Had it occurred to me to submit any of my music I wouldn't have know where to start. It is this naiveté, this youthful innocence (and, yes, ignorance), that contributed in to the tone and spirit of Night of Silence. There was no agenda. No vision for distribution. No intended publisher. No profit motive. Just the raw desire to innovate an expression of Advent and the need for some self-healing. This state of mind is something I have since found difficult to recreate. Once a composer is published and has experienced even a hint of success they risk being less free. It is difficult to ignore things like marketability, industry trends, and customer needs. Of course these are valid things to consider when composing but they can also get in the way. A lot of noise is introduced to the process that can take one from their heart to their head. I wasn’t burdened by any of these tensions when I composed Night of Silence.

Shortly after signing the contract I was approached by the Wenger Corporation to work in their newly formed music software division, which would eventually be rebranded as Coda Music Software. I was a member of a small team including Phil Farrand, John Borowicz, James Romeo, and Lowell Fisher to develop and launch Finale, a software product that would revolutionize desktop music publishing. My publisher, GIA Publications, even made a visit to our offices during its development. They were curious about the work we were doing. I recall a member of the GIA entourage telling us “publishers will never use this.” He doesn’t work at GIA anymore.

the music grows up

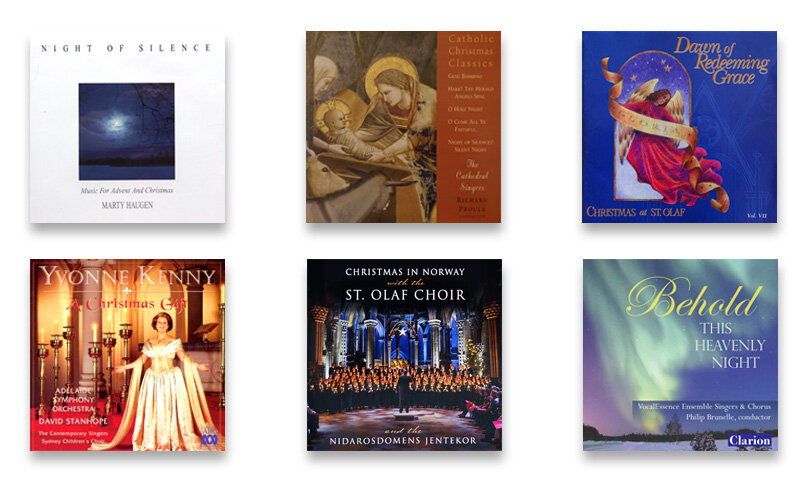

In the late 1980s Marty Haugen would record Night of Silence as the title track to his classic Christmas/Advent CD, introducing it to thousands of his followers. A few years later John Ferguson of St. Olaf College would premiere his arrangement at the annual St. Olaf Christmas Festival, putting Night of Silence on the national stage with broadcasts on PBS television and NPR. I have John to thank for seeing the potential Night of Silence had for larger concert settings.

Recordings and performances by singers, orchestras and choral ensembles from all over the world soon followed. Most recently the St. Olaf Choir featured Night of Silence on its Norway tour, a concert experience now available on Blu-ray DVD.

St. Olaf Choir, Trondheim, Norway

Around the world Australia's famed soprano Yvonne Kenny featured a lush arrangement of Night of Silence on a CD titled A Christmas Gift. Night of Silence was beginning its crossover from liturgical music to a much broader audience, a trend that continues to this day.

More recently, Philip Brunelle's VocalEssence included Night of Silence on its Christmas CD, Behold this Heavenly Night, a masterful collection often heard on NPR each holiday season. And for choral music purists, an a cappella arrangement by Jocelyn Hagen was premiered recently by Matthew Culloton's group The Singers, one of the finest professional choirs in all the land. Jocelyn's provocative adaptation of Night of Silence is a mystical re-imagining of the piece, further expanding the Advent soundscape. There are even two different handbell arrangements for Night of Silence.

Night of Silence is no longer my own. Was it ever just mine? Its origins belong to so many, both during its conception and after. It is a piece people love to make their own, as demonstrated by the numerous published arrangements available. My role is now that of a steward which is one of the reasons I built this website.

As I look back at the year I composed Night of Silence, I’m struck that one of my most successful pieces would be produced in the thin margins of a busy college semester. There were some who argued I shouldn’t have been spending any time composing. Why hadn't I been practicing piano instead? But when logic dictated I had a responsibility to more pressing academic concerns, I listened to my heart. I followed an inner voice that guided me to a composition that would transcend virtually everything else I would accomplish while at St. Thomas. I needed a taste of joy and freedom to create on my own terms and I didn’t look to anyone for permission to do it. This turned out to be a great life lesson.

We are all pilgrims on a journey and sometimes we find ourselves in places we'd rather not be. It is through ritual that our journeys may be deepened and enriched. We live from one season to the next, through cyclical traditions that help us mark time, that ground us to the familiar while connecting us to our past and to those with whom we share our pilgrimage. Of all the ritual seasons, Advent is the one that will always resonate with me on a deeper level—a season that encourages us to embrace a way of being that is out of sync with what our culture tells us.

Yes, Advent is about preparation and anticipation, but it is also about making room for the new. When I composed Night of Silence I cleared a space for what now feels like a fountain that never runs dry. I continue to be filled by connections with amazing people, and the blessings of new and surprising experiences. That is the power of Advent. It first calls us to a spiritual presence grounded in quiet emptiness and expectant hope, and then asks us to trust in this silence. Night of Silence is my expression of this. Beginning in the darkness it guides us to that moment when dawn breaks and a morning of endless possibility awaits.

– Daniel Kantor